The Surrender of Appomattox Court House Easy Videos

NPS

Appomattox Court House NHP Virtual Tour: An introduction to the sites of the park, their role in the surrender, and common misconceptions about their history. Nothing can truly substitute an in-person interpretive experience, but the goal here is to provide some of the meatier and most important theme and information about the park, either for those unable to visit or as a springboard for visitors to ask further questions.

NPS

To all virtual visitors of Appomattox Court House National Historical Park: welcome! Whether you're unable to visit us due to circumstances of distance or time, or you're planning a trip and are just looking for an introduction to the park before you arrive, our hope is that this virtual tour of Appomattox Court House NHP will help to show you some of the rich history that the park has to offer. Feel free to contact us at the park for more information.

What is this place?

At the time of the Civil War, around 140 people lived here in the village of Appomattox Court House, the county seat of Appomattox County, which had formed in the 1840s around the Clover Hill tavern as a stagecoach stop on the Richmond-Lynchburg Stage Road. During the Civil War, more than half of the county's 8,900 inhabitants were African American, almost all of whom were enslaved. Although many of the young White men of the area eagerly enlisted in the Confederate Military, this rural area was relatively sheltered from the momentous campaigns waged in other parts of Virginia and the South. Nobody expected that such a small, insignificant settlement would host one of the most important events in American History.

Tom Lovell

What Happened Here?

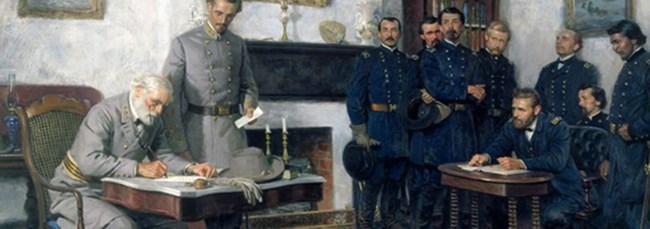

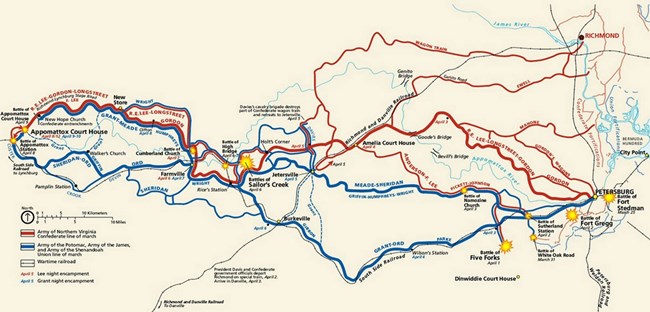

After a week-long campaign pursuing Confederate General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia, three United States armies under the command of Lt. General Ulysses S. Grant finally surrounded Lee at Appomattox Court House on April 9th, 1865. After one last thwarted attempt to break through Grant's lines, Lee realized that he had little choice but to surrender his army. That same afternoon, the two generals met in the parlor of Wilmer McLean, where Grant allowed the Confederates to return undisturbed to their homes and formally dissolved the Army of Northern Virginia.

Why Does it Matter?

Militarily, the dissolution of Confederacy's most prestigious and successful army signaled the beginning of the end of the Civil War: other Confederate generals followed Lee's example in the weeks and months to follow and surrendered to their Federal counterparts. But the significance of Appomattox goes far beyond the movements and strategies of armies and generals. The surrender at Appomattox also saw the first steps towards social and political reunion and reconciliation between former Confederates and the rest of the country, ensuring the survival of the United States and its trajectory towards becoming a stronger nation in decades to come. In addition, once the United States restored its jurisdiction over the area, all of the 4,600 enslaved African Americans of Appomattox County were freed. As such, in years to come, April 9th was celebrated locally as Freedom Day. By the end of 1865, the 13th Amendment to the US Constitution would abolish slavery in the United States.

• What is there to See?

Appomattox Court House National Historical Park consists of about 1,700 acres of land. After parking and entering up the hill to the village proper, visitors can get oriented at our visitor center/restored courthouse building. The McLean House where the surrender took place has three rooms which visitors can explore as well as its outbuildings. There are other historical buildings which you can enter and look inside, including the Clover Hill Tavern and Meeks General Store.

In addition to the village itself, the park's property includes several miles of hiking trails and pull-off sites along Route 24 showcasing the sites of Grant's and Lee's headquarters, a monument to North Carolinian servicemen, a cemetery with 19 soldiers' graves, and a marker for Joel Sweeney, the inventor of the modern banjo.

NPS

1. Visitor Center/Courthouse

Courthouses like these were the center of rural county life in the mid-19th-Century. During monthly 'court days,' free people would meet for adjudication, local government proceedings, and auctions, including those of enslaved people. Appomattox County was formed in 1845 out of territory from the four surrounding counties in order to make these court days more accessible for locals. As with other villages in the state at the time, it was the role of this village as county seat and the location of the important courthouse that gave it its name: Appomattox Court House.

When Lee's and Grant's armies arrived here on April 9, 1865, following a week-long campaign, not only was it not court day, but it was actually Palm Sunday, so the courthouse was closed. It was for that reason that Grant and Lee ended up meeting in the parlor of Wilmer McLean's house rather than in the courthouse building.

The original courthouse burned down in 1892, destroying a wealth of records about the local population and its history. The National Park Service completed reconstruction of the building for use as a Visitor Center in 1965

NPS

2. McLean House

Wilmer McLean's famous quip that "the War started in my front yard and ended in my front parlor" is partially true: the McLean family owned property near the battlefield of 1st Bull Run/Manassas. Still, the McLeans were not present at the time of that battle and did not move to Appomattox until two years later, primarily to access the railroad at Appomattox Station to facilitate Wilmer's sugar speculation business.

That Sunday morning when Lee agreed to surrender his army, McLean was one of the few White men out in the village when Lee's aide Lt. Colonel Charles Marshall came looking for a place for the opposing commanders to meet for the formal surrender. McLean at first suggested meeting in the former Raine Tavern However, since it was abandoned and unfurnished, Marshall deemed it unsuitable and McLean reluctantly agreed to let the men meet in his parlor.

From 1:30 to 3:00 on the afternoon of April 9th, the generals met in the McLean parlor, seated at separate tables. Following President Lincoln's initiative to make the return of former Confederates into the Union go as smoothly as possible, Grant drafted generous terms that allowed Lee's Confederates to return home rather than be taken prisoner. In addition, officers could keep their side arms and enlisted men were allowed to keep their horses to make farming easier. In addition, Grant offered his extra rations to the hungry Confederates who had had little time or opportunity to eat in their weeklong march from Petersburg and Richmond.

NPS

3. Lee-Grant 2nd meeting site

Although Appomattox saw the end of the Army of Northern Virginia, it was not technically the end of the Civil War. As Lee surrendered, there were still prominent Confederate armies in the field in North Carolina, Indian Territory (Oklahoma), and Texas. Knowing that Lee had recently been made commander-in-chief of all Confederate armies, Grant met with the Virginian a second time on the morning of April 10th at this spot to ask him to surrender the other armies and bring the war to as speedy an end as possible. However, Lee demurred, citing his deference to Confederate President Jefferson Davis, had urged the war to continue. The surrenders of the remaining Confederate forces took weeks and months, and hundreds more soldiers on both sides died in aimless skirmishes. The last "battle" of the Civil War took place from May 12-13 in Texas, and the last "surrender" was of the Confederate commerce raider the CSS Shenandoah, which surrendered in Liverpool, England on November 6th.

While their meeting did not resolve the matter of other armies, during the discussion Lee mentioned the possibility that his men may be mistaken for deserters by other Confederates. As such, Grant agreed to print out parole passes for the approximately 30,000 Confederates present to allow them to return to their homes unmolested.

NPS

4. Clover Hill Tavern

Taverns in the 19th-century functioned more like a modern hotel than a bar, and were important stops for travelers traversing paths like the Richmond-Lynchburg Stage Road. The Clover Hill Tavern is the oldest building in what would eventually become Appomattox Court House. Originally built in 1819 by the Patteson family, who also operated the nearby stage line, by the time of the surrender in 1865, the tavern was owned by the Hix family. In addition to the main tavern building where guests would eat, drink, and socialize, the Clover Hill Tavern had an outdoor kitchen, slave quarters, and a guesthouse for weary travelers to spend the night. Today the bar room and dining room are gone, but the other outbuildings serve new purposes as our bookstore, restrooms, and park storage buildings.

Armies, like all government departments, regularly navigated layers of bureaucracy and paperwork: dispatches, reports, intelligence, rosters, etc. Printers and their equipment were an important part of an army's logistical staff. Grant assigned some of these printers to set up their presses here in the Clover Hill Tavern soon after his meeting with Lee on April 10th. There US printers worked through the night and into the morning, cranking out tens of thousands of blank parole passes to distribute to Confederates in accordance with Grant's promise to Lee. Running down the rosters of their men, Confederate officers listed the soldier's name, state, company, and regimental designation before signing at the bottom. The park maintains an alphabetized list of all the parolees both in a physical copy and on our website.

In addition to signifying to other armies that the parolees were neither deserters nor combatants, these parole passes could be used to receive free transportation on a US-controlled railroad, steam ship, or stagecoach in order to help the men get home faster. It could also be used to receive free rations. A great many former Confederates took advantage of the free transportation, but many others preferred to walk, either because their homes were close or because they were in no mood to take Northern charity.

NPS

5. Richmond-Lynchburg Stage Road

Until the emergence of nearby Appomattox Station in the mid 1850s, this road was the main artery of the county and village through which travelers and goods passed via stagecoach between the major cities of Richmond and Lynchburg on the two sides of Virginia. Appomattox Court House grew around the vital road, and as the railroad replaced the stage road in prominence, the village begin to wither and die.

On April 12, 1865, the 22,000 Confederate infantrymen of the defeated Army of Northern Virginia, under the command of Major General John B. Gordon, marched along this road, division by division, from the McLean House to the east side of the village, stacking their rifles and folding up their flags. About 5,000 Federal soldiers lined the sides of the road to oversee the process under the command of Brigadier General Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain of Gettysburg fame. As a token of respect and conciliation to his defeated foes, Chamberlain ordered his men to shoulder arms. Moved by this gesture, Gordon ordered his men to reciprocate. Thus, the two enemies departed not with jeers and taunts but with solemn silence and mutual respect.

NPS

6. Confederate Cemetery/UDC Plaque

Buried here are 18 Confederate and 1 US soldier, only 8 of whose names are known. These men were among the approximately 300 soldiers of both sides who died during the Battle of Appomattox Court House, mere hours away from peace and a chance to return home.

Long after the guns of Appomattox ceased fire, however, the Civil War has continued to be fought on the battlefield of popular memory. One of the most significant salvos of that war of ideas was fired by Southern organizations like the United Daughters of the Confederacy, who used censored textbooks and the widespread erection of plaques and monuments to glorify and defend what has become known as the "Lost Cause of the Confederacy." This Lost Cause view of the Civil War ignores the centrality of slavery as a direct cause of the Civil War, romanticizes antebellum plantation life to downplay the cruelty of slaveowners, and seeks to delegitimize the ultimate US victory by claiming that the result of the war was a foregone conclusion due to the overwhelming numbers and resources of the North. This UDC plaque showcases this latter aspect of the Lost Cause. The 9,000 Confederates and 120,000 US forces (the park removed this line in the mid-20th century) which it cites are notably inaccurate. There were approximately 60,000 Federal troops at Appomattox, and the park has a list of 28,000 Confederate soldiers who received parole passes.

Plaque by cemetary

NPS

7. Kelley/Robinson House

Even in rural Appomattox, which saw very little of the actual war until the very end, it was impossible to find a household that wasn't touched directly or indirectly by its effects. One such household was the Kelley family, who sent five of its sons to fight for the Confederacy. Of those five, two died, one was injured, one deserted, and one was present here for Lee's surrender. The story of the Kelleys is representative of the many ways in which the war forever changed the lives of ordinary families, North and South. Some sons and husbands never came home, and those who did would never be the same.

To the Kelleys, this house was a monument to the pain, loss, and despair that the war had brought to their families and to the Confederacy. But after the war, this same house was a monument to the hope and promise of a new class of Americans seeking to assert their independence, initiative, and sense of community in uncharted waters. More than half of Appomattox County were enslaved by the time of the surrender, and to these individuals, the surrender at Appomattox meant immediate freedom, with all of the opportunity and uncertainty which that entailed. One such freedman, John Robinson, purchased this home in 1871, where he managed a cobbling business alongside his family. Robinson was one of the foremost founders of the Galilee Baptist Church, the first African American church in the county.

8. Erected by North Carolinian veterans 40 years after the surrender, the monument marks the place where the North Carolinians claimed to fire the last volley of the Army of Northern Virginia during the war. The monument boasts of the Tar Heel State's status in the war as "First at Bethel," "Farthest to the front at Gettysburg and Chickamauga," and "Last at Appomattox." Among the list of Confederate parolees, we have the names of approximately 5000 North Carolinian soldiers who were surrendered on April 9, 1865.

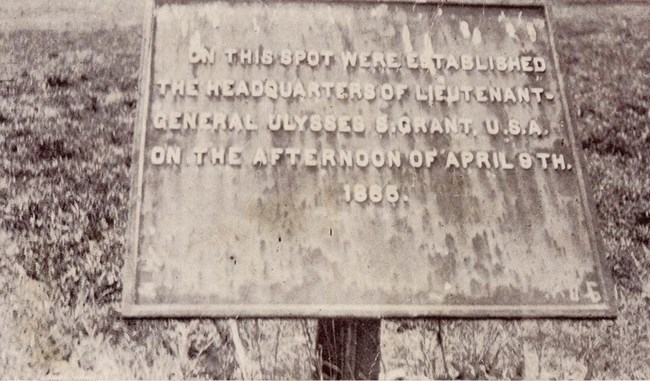

9. Grant's HQ

The morning after his victory at Sailor's Creek(https://www.dcr.virginia.gov/state-parks/sailors-creek--state park web address) on April 6, 1865, Grant began a correspondence with Lee in an effort to convince him to finally surrender the Army of Northern Virginia. From then until the surrender meeting itself, the two generals exchanged letters. Lee declined to surrender his army but suggested discussing a political end to the war with Grant, probably in an effort to gain better terms. As a soldier rather than a politician, however, Grant did not believe that he had the authority to discuss a political end to the war and only had the ability to discuss the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia.

After the Battle of Appomattox Station on April 8th, Lee sent Grant a letter in which he declined to surrender his army but which asked Grant what terms he might offer. Grant replied that the Confederates would be "paroled."

The next letter Grant received was on the morning of April 9th at his headquarters at Clifton some 20 miles from here, shortly after the Battle of Appomattox Court House. He had been suffering from a migraine headache all night, but he later said that the moment he received Lee's letter, in which the Confederate leader agreed to surrender, the migraine instantly disappeared.

After the meeting with Lee, Grant rode to this spot where he established a temporary headquarters. He had been so preoccupied by the day's momentous events that he didn't realize until later than he had forgotten to inform Washington of his victory. From here he sent a messenger to Appomattox Station to relay a telegraph message to the White House. Within a few days the entire country knew about Grant's victory.

NPS

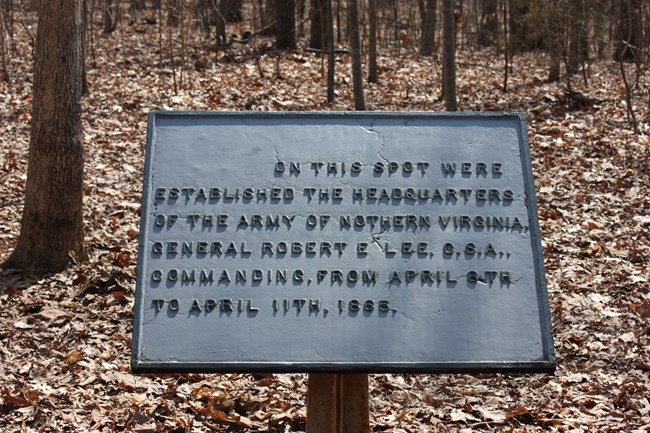

10. Lee's HQ

Lee held one last council of war before he ultimately decided to surrender his army. As he was outnumbered and surrounded, he only really had two options at his disposal: he could prolong the fighting and suffering by breaking his army into guerrilla bands, or he could finally surrender. Ultimately, Lee realized that the former option would merely delay the inevitable and cause needless bloodshed and destruction. "Then there is nothing left for me to do but to go and see General Grant," Lee said. "And I would rather die a thousand deaths"

After Charles Marshall returned having chosen the McLean House for the generals to meet, Lee dressed himself in a fresh new uniform before leaving his headquarters, explaining to an aide that he ought to look his best as he expected Grant to take him prisoner.

When he returned to his headquarters after the surrender, Lee had Charles Marshal draft General Order #9, a farewell address to the Army of Northern Virginia. In it, Lee expressed his gratitude for his men's loyalty and courage over the duration of the War and explained that his decision to surrender was to avoid unnecessary bloodshed. Copies of the order were distributed throughout the army. Lee never read them to his men.

The first line of the General Order, which states that the Confederates were "compelled to yield to overwhelming numbers and resources," was influential in the development of the Lost Cause narrative's insistence on inevitability of the Confederate defeat.

Source: https://www.nps.gov/apco/learn/virtual-tour-of-appomattox-court-house.htm

0 Response to "The Surrender of Appomattox Court House Easy Videos"

Post a Comment